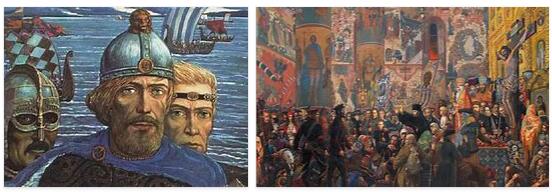

The history of Russia, as an attempt to unify Slavic lineages under the leadership of a strong monarchy, begins in the mid-century. IX, when some Slavic populations of northern Russia, together with groups of Swedish settlers based in the same region, turned to the Normans of Scandinavia to intervene to protect them against the Chazary nomads advancing from the east. The invitation was accepted by the Danish Rjurik who settled in Novgorod (856) and from there sent an expedition to conquer Kijev and, later, to threaten Constantinople itself with the help of other Swedes who had formed a state of warriors and merchants around the Sea of Azov. It was therefore the Normans, called in Russia Vareghi or Variaghi, who gave birth to a certain unitary drive in the Slavic tribes and started them towards the formation of a vast state team between the Baltic and Black Seas. The successors of Rjurik – Oleg (m. ca. 911), Igor (d. 945) with his wife Olga (d. 969), Svyatoslav (d. 972), Jaropolk I (d. 977), Vladimir I (d. 1015), Svyatopolk I (d. 1019), Jaroslav I (d.1054) – all but the first, descendants of him, made Kijev the capital and center of their principality, which included a large number of Slavic tribes from the Gulf of Finland and from the lakes Onega and Ladoga to the Sea of Azov and the Caucasus, from the Pripyat swamps to the Volga. Warriors of race, they went as far as Constantinople with Oleg (907), they again attacked the Byzantine empire with Igor (941 and 944), they defeated Bulgari and Chazary with Svyatoslav (967-68). Meanwhile Christianity was advancing from the West and was already spreading among the Slavs. Vladimiro chose the path of conversion (988) and officially introduced the Christianity of Byzantium; his descendants in 1054 followed the Byzantines also in stiffening against the claims of the Roman Church and in the schism that followed. This decision was the barrier that for centuries separated Russia from the nations of the West. Kijev, however, remained independent from Byzantium, of which he accepted the doctrine, not the jurisdiction, and was the religious capital before yielding to Moscow. this privilege (XIV century). On the death of Vladimir, the sons fought bloody for the inheritance: Jaroslav managed to reunite the entire principality in his hands and give it new splendor, endowing it – among other things – with a Code (the Russkaja pravda) very remarkable for the his times; but at his death the fights between his children and grandchildren resumed so that the Polovcy (or Cumans), shepherd-marauders of Turkish descent, devastated the Ukrainian steppes for many years. Kijev became impoverished and rapidly decayed, and the energy of Vladimir II Monomachus (d. 1125), who beat the Polovcy and seemed capable of restoring the state, did not help to stop the fall. In 1169 his nephew, Andrea Bogoljubskij, Duke of Vladimir, took the city and sacked it. But both Andrew and his princes allies in the fight against Kijev, continuing to divide their territories among the numerous sons, progressively weakened. The living forces of Russia were then three: the rich merchant city of Novgorod, democratically ruled by an assembly of citizens (veče); the Muscovy, which since sec. XII grew rapidly at the expense of the neighboring duchies; and the Church which, in the anarchy of princes, acquired ever greater influence over the people and expanded its landed possessions.

The capital, other cities (Vladimir, Suzdal, Tula, Pskov, Ryazan, Tver, Smolensk, Nizhny Novgorod etc.) grew in ambition and wealth. But the invasion of the Mongols (1237-41) overwhelmed several of these cities, as well as destroyed the half-resurrected Kijev. Only Novgorod and Pskov survived; Moscow soon got up and later availed itself of the favor of the Mongols to build its greatness. Batu, grandson of Genghis Khān and conqueror of Russia, set up his seat in Sarai on the lower Volga and made it the capital of the khānate of the Qipciāq (or kingdom of the Golden Horde) dependent, at least initially, on the great khān of the Mongols. In this reign, which lasted over two centuries, the Mongols (or Tatars) limited themselves to collecting tributes regardless of the needs of the population and respecting only the Church and the Orthodox clergy; but the Asian imprint manifested itself in certain institutions destined to take root in the Russian land, such as despotism and slavery, and contributed to alienating the Russian civilization from the path of the West for a long time. Mongol domination was not even a factor of unity among the Russian peoples. They developed an autonomous life of their own, outside the Tatar area, White Russia (Belorussia), centered in Smolensk, then subdued by the Lithuanians (first half of the 14th century) and Little Russia (Ukraine), always threatened and repeatedly invaded by Polish forces. Tributary of the Mongols, but substantially independent, Novgorod remained, defended by its prince Alexander Nevsky (d. 1263) who, beating Lithuanians, Teutonic Knights and Swedes, the champion of the Orthodox faith against the papal “crusades” appeared. With Danilo (d.1303), the younger son of Alexander, the rise of Moscow began, favored by the geographical position that allowed it to connect, by river, with the Baltic Sea, with the Gulf of Finland, with the Volga basin and the Caspian Sea and the Black Sea. XIV the princes of Moscow acted as tax collectors in the name of the khān: this office allowed them to make use of Mongolian troops against rival or rebel principalities and above all to enrich themselves to the point of exerting a strong influence on the khān, always haunted by the lack of Cash. All this made the fortune of Ivan I Danilovič Kalita (d. 1341), prince of Moscow; he, severely repressed the anti-Mongol revolt of Tver and other cities of central Russia, enormously expanded his territory, attracting settlers from near and far regions; no less important was the religious consecration of his hegemony, obtained when the metropolitan of the Russian Church, already residing in Kyjev and then in Vladimir, moved permanently to Moscow. Only in the second half of the century. XIV began in Russia a real military offensive against the Mongols, now weakened by internal struggles. In 1380 the Prince of Moscow Dmitry Donskoy defeated the Tartars in Kulikovo in a bloody battle in which contingents from almost all of northern and central Russia participated. It is true that two years later the Turco-Mongols led by a general of Tamerlane attacked Moscow, Vladimir and other cities, devastating them, but a few years later Tamerlane himself, defeating in battle an army of the Golden Horde that had rebelled against him and hitting the old Mongolian khānato, unwittingly prepared the Russian revolt. At the beginning of the century. XV Moscow was still threatened from the east (Mongols) and from the west (Lithuanians): the latter reached as far as Smolensk. But, with the passing of the years, the enemies of Russia eased the siege: it was now up to a resolute and well-armed prince to carry out that process of unification which time and events had now matured.